By Amy Bickel

SHIELDS – From the photograph, a lively town was celebrating the summer of 1925 with an annual picnic.

It seems like the perfect Norman Rockwell setting: women wearing their Sunday dresses carrying an umbrella to obscure the sun; baseball players eating hot dogs and drinking soda at a concession stand, waiting for the game; a Ferris wheel filled with people, ready to spin. In the background a crowd watches a horse race.

Businesses across the county would shut down for the picnic, which drew thousands to the two-day affair that ended each night with fireworks lighting the sky.

However, this isn’t Shields, Kansas, of today.

At 84, Dr. Don Tillotson recalls moving to town as a sixth grader in 1943 – watching the trains go through Shields, heading west with tanks and troops during World War II. He still remembers hearing the artillery from the military airplanes practicing north of town at the gunnery range – even finding a belt of unspent 50-caliber shells in his family’s pasture.

For fun, they’d search for shark teeth in the family’s pastures – which was once part of the Great Inland Sea. They’d also frequent Stewart’s grocery and attended the local Methodist Church. Moreover, Shields grade school helped set the educational foundation for this future doctor.

It was never a big town, but it was a tight-knit community, said Tillotson from his home in Ulysses.

“It’s been a gradual deterioration from that time. It really is a wreck of a town now,” he said sadly.

Yet, several times a year, he comes back to check on the Lane County farmland – largely rolling pastures and canyons that the family still owns.It’s where his great-grandparents first homesteaded. They even ran the general store for a while. It’s where his parents – Raymond and Amy – raised him – forging a life on the Lane County prairie.

“That farm is home to me,” he said. “It’s still a part of my life – very much so.”

Good day for a Shields Picnic

People came to western Kansas from around the world – lured by free land.

Shields was no different. Homesteaders began settling around the Shields area in 1886 – building sod homes due to the scarcity of wood in these parts. Like many early pioneering communities – faith was important, and they they soon established a Methodist Church on the land owned by pioneer John Smith. The church also served as a schoolhouse, according to the Lane County Museum.

But like many towns, life seemed to spring up with the railroad, and the Missouri Pacific came through in 1887. The town was named after nearby settler Richard Shields. Shields’ brother-in-law, by the name of Wilson, was also an area settler and his name was given to the township.

Activity began to bustle. A post office opened in December 1887, according to the Kansas State Historical Society. Sam Allen opened the first store and more followed, including one established by the Wright family and another by John and Maggie Tillotson, according to the Lane County Museum.

John died not long after the store opened in 1897, and Maggie continued to operate it with her son Walter, for several years, according to the historical society.

She farmed on her own for a time, too. The Lane County Journal in October 1897 said she shipped a carload of wheat of her own raising. The store also had a second story called the Tillotson Hall, where folks enjoyed plays and, eventually, movies.

Maggie Tillotson eventually closed the store when her son was drafted, according to the Lane County Museum, but more stores followed. Around 1921, George Maddy and Eugene Terwilliger celebrated their grand opening by offering everyone who entered a free ice cream cone, followed by a band and a baseball game played in the afternoon, according to Ellen May Stanley’s book “Golden Age, Great Depression, and Dust Bowl.”

Shields even had a tennis court, along with a garage, restaurant and cooperative elevator. The Farmer’s State Bank was built in 1916. It was small, but thriving in 1910. According to the book “Kansas: A Cyclopedia of State History,” Shields had a population of 48 and several businesses – general stores, the post office and telegraph and express offices.

But the entire county, and its neighboring ones, it seemed, flocked to the Shields Picnic, which first started in 1920 and was a successful annual event – complete with band, carnival and other entertainment, according to the museum.

It was still going in 1931, and included boxing, and there also were baseball games and horse racing.

Yet, by the 1930s, Shields was fighting the dust just like any western Kansas town – as well as poor crops and economy. Residents also fought fires, including one in 1935 that burned the Robinson elevator and the Davidson Mercantile.The fire’s origin, according to Stanley’s book, was supposedly because of spontaneous combustion from the electric winds and dust.

The annual picnic eventually ended, most likely sometime in the 1930s, said June Wick. She and her husband, Howard, were longtime Shields business owners. Howard has memories of attending the event.

Gradual decline

On a June afternoon, Brooks Wick pulled into the area where his family’s rundown grain elevators still stand – bins on each side of the road going into town. His father, Dan, was just down the road, cutting wheat.

Until the early 1990s, his family binned area farmers’ crops here. Nowadays, the territory is taken up by a large cooperative.

Brooks’ grandmother June, 86, said the family operated the grain elevators for years. They sold fertilizer and ground corn, too.

But by 1992, her husband retired. The elevators weren’t in good shape for taking grain anymore, and their son was allergic to wheat dust.“We had good customers and loyal customers,” she said.

In November 1994 the death knell sounded. The post office closed.

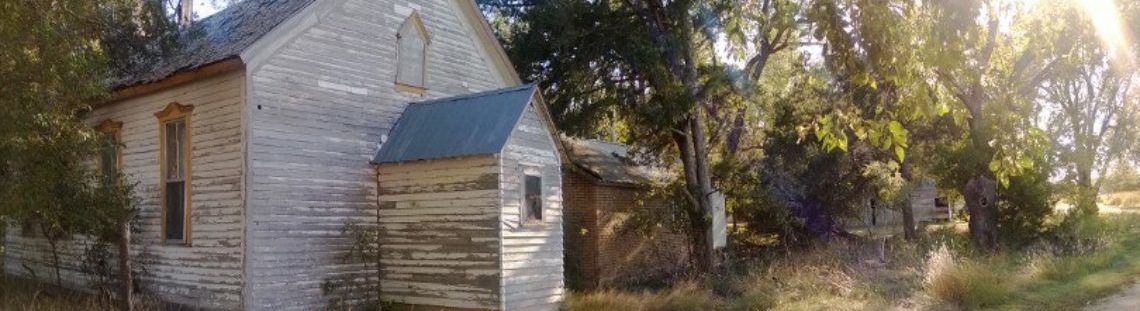

Today, the school still stands. So does the paint-stripped Methodist Church – which had its last service in the 1980s. Stewart’s store is gone. A few occupied houses remain.

Shields has been hit by progress.

Shields was declining when Tillotson’s family moved to the area in 1943. The bank and a few other businesses had shuttered. The picnics of the past that drew thousands had stopped years before then.

His father, Raymond, grew up here, went to college, got a master’s degree and worked for the Soil Conservation Service in the 1930s, moving his family around western Kansas. He eventually got the opportunity to take over the family farm from his father, Warren, moving his family back to Lane County.

Don went on to the University of Kansas medical school to follow another dream of becoming a doctor.He recalled his first day of grade school at Shields, and how some of the boys in class had started a paper-wad fight while the teacher helped individual students with their work.

“He seemed like he ignored it completely,” said Tillotson of the teacher, but added at recess he stood at the outdoor steps of the school and grabbed each hooligan by the ear.

“He gave them a good shake,” he said, adding he doesn’t remember any other issues from the classroom after that.

Tillotson tried to stay on the farm after going to college. But in the 1950s, there wasn’t enough income to support both himself and his parents.

“The thing that attracted me to medicine was I spent a lot of time as a kid being a doctor’s patient,” he said. “I had some health problems, and that led me to medicine as a career.”

Howard Lawrence, 78, a fourth-generation farmer whose ancestors homesteaded in Lane County, said he lived in the Shields area since he was two years old and attended the brick elementary school all eight years. His children went to school there, too, and his son still farms and ranches in the area.

After school, many students would go to Stewart’s store for a pop while they waited for their parents to pick them up, he said.He recalled people taking cream to the depot every evening to ship out. For a long time, the mail came by train, too.

Largely what is left of Shields is memories.

“It is just the way things are,” Lawrence said. “People have to find a way to make a living. They go somewhere else.”