When COVID hit in March 2020, my twin daughters were in the middle of studying Kansas history.

Among their virtual assignments was to learn about Kansas settlement, including about Exodusters who came to the state after the Civil War.

Tasked with writing a report about the subject, I told them we should just take a field trip and learn more.

So, on a cloudy, early April morning, we headed toward the Morris County ghost town of Dunlap.

The spirits of this Exoduster colony are still visible in Dunlap

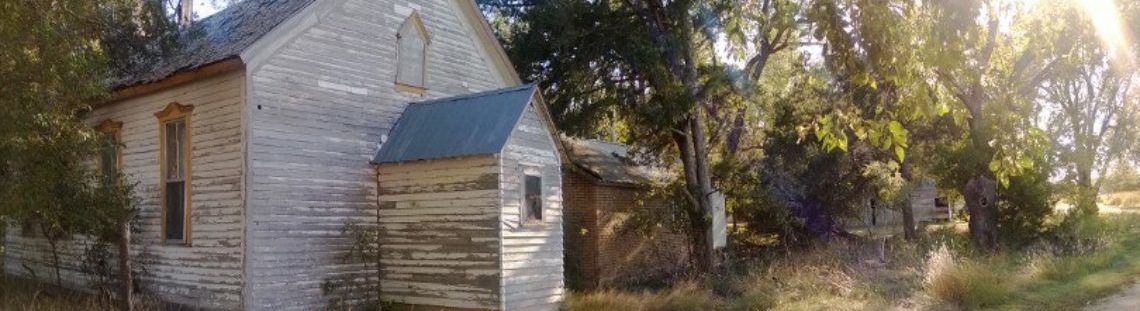

The African-American history here exists only in traces – mostly a few wayward gravestones and dilapidated structures.

The the old Baptist church where parishioners once sat in the pews was standing the last time I was here – a few pews remaining in the building along with a piano. It was now a collapsed pile of rubble.

Dunlap, a tiny town in southeast Morris County – population 20 – was home to a few hundred African-Americans – “exodusters” who left the post-Civil War South looking for new land and a new life.

The last African-American resident, London Harness, died in 1993, his grave one of the few marked by flowers.

There were several Exoduster communities across Kansas. I’ve been to three, including Morton City in Hodgman County, Nicodemus in Graham County and Dunlap, which I made my first trip to around 2000 for a story for The Emporia Gazette.

Little remains at Morton, which I had the chance to visit when I worked for The Hutchinson News. I was guided by a descendant of a founding resident. Nicodemus is a National Historic Site operated by the park service. It’s a great stop for those traveling through western Kansas. Dunlap is just one of the ghost towns in the Flint Hills of Kansas – communities that once prospered at the turn of the century. Yet, while Dunlap’s community died, the history is still there for those who look closely.

Names, some scratched into stones in the cemetery, tell part of the community’s history.

Some of the residents, former slaves, served in the war and fought for their freedom. Then thousands of them went west, including to Kansas – searching for a better life, according to the Kansas State Historical Society.

In 1879, Pap Singleton founded the Dunlap Colony, located next to the white community of Dunlap, according to “Exodusters: Black Migration to Kansas.”

Because Kansas was famous for John Brown’s efforts and its struggle against slavery, Singleton considered the state a new Canaan, and he led people to the promised land, including around 200 to Dunlap.

The town had businesses and the Dunlap Academy for African-American students.

In 1880, with the help of the Associate Presbyterian Synod of North America and the Freedmen’s Aid Association of Dunlap, “The Freedmen’s Academy of Kansas” formed. Its mission was “to educate the colored youth for teaching, for business management, for mechanical industries, for an honorable social life, and to encourage settlement of destitute colored families of the cities on cheap lands in the country.” Upon completion of the academy, a student would be ready to attend freshman classes at a university.

But like many rural communities, people moved away. Harness was the final link to the past, the last to represent the generation of exodusters who made Dunlap their home. Nearly 200 African American residents are buried in Dunlap’s cemetery, including many in unmarked graves. “My grandparents are buried here.” Harness was once quoted as saving. “I’ve helped bury many of my friends in this cemetery.”

Today, the community has numerous abandoned buildings, including a large gymnasium, paint-peeling houses, concrete foundations testifying to more prosperous times.

A history lesson

I‘ll have to admit, my daughters were skeptical about taking the trip. They don’t share my love a ghost towns as much I would like them. The girls, and especially my husband, have been on too many unexpected side trips where I’m out taking photos happily of a dilapidated building – mesmerized in the hopes and dreams – while they don’t think it is quite as cool.

But as we stood in the African-American cemetery on the hill north of town – with the wind whipping the well-kept prairie grass dotted with stones — located not far from the “white cemetery,” they began to comprehend the trials of the early settlers here.

And, we could see the colony’s spirit is still very much evident.