By Amy Bickel

Originally printed May 30, 2017 by The Hutchinson News

It wasn’t a lackluster attitude that killed Nonchalanta.

When luck ran out, so did the residents.

But along this dirt path in southern Ness County, stone ruins still remain – sort of a grave marker amid the cattle pasture Harlan Nuss has rented for several years.

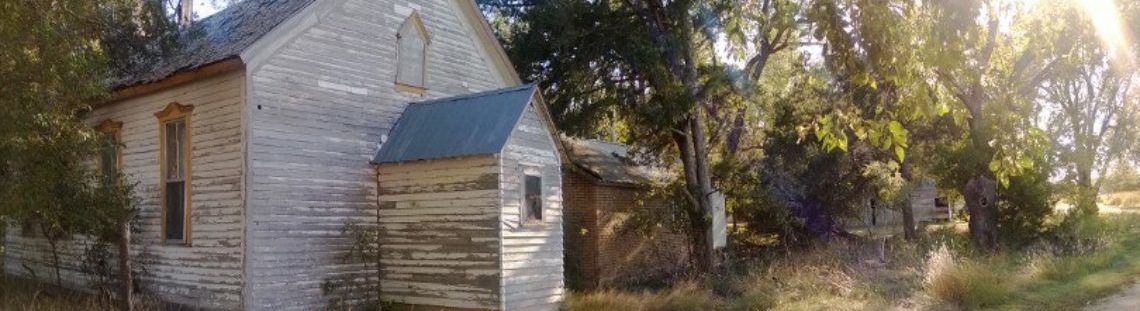

On a gray Sunday afternoon, Nuss led a small tour of the former town site. He scoped the surroundings, which included an old livestock barn, a dilapidated hotel and falling down schoolhouse, murmuring it is hard to imagine there was ever a town here.

Non-chalanta, in fact, was like many Kansas ghost towns – it sprouted liked a weed on the prairie. It busted for a few years. Folks built a school, church and a hotel, along with other businesses. Work began on a bank, and there was even a post office – giving the town the official stamp of existence.

But five years later, the death knell sounded.”The railroad was supposed to come to town,” said Nuss, noting the town grew with that anticipation. “When it didn’t come through, the town pretty well folded.”

Just give it a “d—” name

With the promise of free land, Fred Roth and his family came in covered wagons from Missouri to Ness County.

So did others. John Silas Collins, a circuit-riding Methodist minister, who arrived in 1879 and began work to prove up his homestead, according to an article by local historian, the late Jan Gantz, which was published in the Ness County News.

They began building sod homes and plowing up the grass.With pioneers came the need for a town. Homesteader Lewis Odom in 1885 decided to plat a town and asked another local, Dr. W.A. Yingling, to come up with a name.

“And I don’t care a d- – what kind of name it is, just so it’s a taking name,” Odom told Yingling according to several historical articles.

So, as the tale goes, Yingling called it Nonchalant, after the French word of that very idea, and then decided to add the “a.”

Odom loved it and began promoting Nonchalanta with the idea the railroad was coming. One newspaper printed on May 23, 1885: “New town of Nonchalanta laid out.” By September, lots were reported to be selling for $15 to $85, according to the book “Ness, Western County, Kansas” by MinnieDubbs Millbrook.

Momentum continued and folks prepared for a promised railroad. Nonchalanta would soon have a livery, a drug store, three-story hotel, real estate office and a general store, Gantz wrote in her article. There was a Methodist church and newspaper. A quarter-mile away, a man named McCandish operated a small country store and post office that the government had previously dubbed Candish. By 1887, the post office was renamed Nonchalanta.

In fact, said Wichita resident Cheryl McVicker Lewis, whose family homestead in the area, the Nonchalanta newspaper from August 1887 showed 22 businesses advertising in it.”And it said there were also several more carpenters, two more blacksmiths and several stone masons and plasters,” said Lewis, who grew up near the town site and has researched local and family history. “There were plans to build 100 houses in the next six months.”

Folks had began construction on the bank, as well as more stores, restaurants and a Grand Army of the Republic post. There was even talk of a summer resort called “Wildhorse Lake” – located around a natural depression where the wild horses would water, wrote Gantz.

Gantz also reported that lots were advertised in Folsom Heights – “a beautiful suburb overlooking the city.”And, in 1887, according to the book by Millbrook, the newspaper advertised the town as “the magic young city of the plains, with six public wells with pure water, a hundred houses to be built in early spring and a railroad to be built during the coming summer.”

Sam Howell was one of the business owners. According to family history, he worked on the railroads across western Kansas, drove freight and was employed on area ranches before homesteading and starting a feed store in Nonchalanta.

There he met Susie Helen Corbet, a young girl working at the Nonchalanta hotel, which was operated by John Rogers, a man who would later become governor of Washington, according to Corbet’s writings discovered by Lewis.

Susie and Sam married in Nonchalanta in April 1888 – the same year the school was finished.

The town was buzzing.

“Dancing, baseball games and picnics were part of the entertainment,” wrote Gantz.

Survival

Survival, however, became work in itself.

Settlers struggled but made it through the blizzard of January 1886. But a Mr. Cooper died of a rattlesnake bite, John Abrahams was killed by lightning and a Newby boy froze to death. Meanwhile, rain didn’t follow the plow – like advertised – especially in these parts where the average rainfall is 17 inches a year.

The Nonchalanta Herald, which issued its first paper on May 20, 1887, went out of business on Feb. 8, 1889, losing hope that the promised railroad would come.

“By 1890, little was left of Nonchalanta, but the ghostly stone buildings,” Millbrook wrote.

Some activity continued

The Slagle family, however, were among some of the homesteaders who stayed in the area, said Lewis.

Her great-grandfather, George Slagle, ran the store in Nonchalanta for a time. An article in the Ness County News from spring 1894 reported he turned over the “groceries” to another man and moved back to the homestead east of town.

That fall, he moved his family to a stone house west of Nonchalanta.

A tornado in 1899 may have taken the third story off the hotel, said Tom McCoy, Lewis’ cousin. Meanwhile, the family living in the hotel ran a general store in the area, which was open a few decades after the town depopulated, said Nuss.

The post office eventually moved to Lewis and McCoy’s great-grandfather George Slagle’s rock home located a few miles away. Built on a hill using the limestone of what was to be the Nonchalanta bank, folks could walk into the basement doorway to get their mail, Lewis said.

Part of the basement was for the family’s apple crop – which, one season, totaled about 700 bushels of apples, said McCoy.

The post office closed in 1930, according to the Kansas State Historical Society.

Lewis’ father, Dean, and sister, Mary McVicker McCoy – Tom McCoy’s mother, recalled visiting their grandparents and watching George put out the mail, “but weren’t allowed to go in,” Lewis said.

Reclaimed by the prairie

On this winter day, Harlan Nuss, Tom Reed, who hails from the nearby ghost town of Ravanna, and McCoy, traipsed about the pasture Nuss rents where the town once stood.

Except for his grazing cattle and the rattlesnakes that make their appearance in the heat of summer, there is nothing much happening in Nonchalanta, Nuss said.

“There may have been 300 people,” said Nuss, but added with just the tales that are passed down and everyone from that era dead, he doesn’t know for sure.

McCoy said he remembers visiting the Nonchalanta school in the mid-1940s while a cousin was attending. It closed in 1946. Nuss said it was turned into a farm shed before falling into disrepair.

The school is one of the remaining ruins on the prairie. McCoy, on the recent Sunday afternoon, pointed out the names of schoolchildren carved into the stone walls are still visible after all these years.

Many would carve their names and initials, despite the teacher scolding them for it, said Lewis. Somewhere amid the rubble is the name of Lewis’ father, Dean.

“He had been home sick … and his sister came home and told him you are in trouble,” she said, noting the teacher must have discovered the carving. “He had to stay after school the next day.”

Nuss said he often finds rocks where foundations might have been, as well as a few of the spots where city wells were located. There is a large depression at the site of the bank.

Nuss sometimes thinks about the area being a town center as he is checking cattle.

“It makes you wonder what it looked like and stuff – what the houses looked liked,” Nuss said.

Lewis tries to envision the town, too – a town with homes, businesses and streets with names like Warren, Heath and Union.

Now, except for the few stone structures, Nonchalanta has been reclaimed by the prairie.

“I just can’t imagine what that looked like in 1887 considering how it looks now,” she said.